Transient Ecologies

November 5, 2012

Is something that is beautiful also good? Worthy of striving for? Is beauty truth? If beauty is nothing but a sweet lie, is goodness the same? Is it good to strive for beauty? Is it beautiful to strive for goodness? I now think that beauty and goodness are not beautiful and good in themselves, but that striving for them may be beautiful and good. Striving for something is at odds with the fulfillment of that striving. An aspiration fulfilled becomes ugly and evil because it demands sacrifices and kills desire.

Hans Op De Beeck, “Spa”

November 5, 2012

Nowhere and at no time is form the result achieved by finishing, or concluding. It must be seen as a genesis, as movement. Its being is in becoming and the form as appearance is only a malicious apparition, a dangerous phantom.

Form is good as movement, as doing, as form in action. Form is bad as inertia, enclosed in a final stop.

Form is the end, death.

Formation is life.

Paul Klee, “Pedagogical Sketchbooks”

November 5, 2012

Scales of Impermanence

In a hundred years everybody here – me included – will have disappeared from the face of the earth and turned into ashes or dust. A weird thought, but everything in front of me begins to seem unreal, as if a gust of wind could blow it all away.

Haruki Murakami, 2003

Having realized the weakness of permanence as a motivator, Architects have endeavored into the realm of the impermanent. Contemporary impermanence can be typologically categorized as portable and ephemeral. Portable impermanence can be further subcategorized into transportable and mobile, while ephemeral can be subcategorized into pneumatic, festival, fragment, and material.

TRANSPORTABLE

“Nearly every American house I’ve lived in has long ago been demolished to make room for some other building. There is a delicious (though painful) paradox here: Americans long for stability, but all they get is stationary impermanence. No wonder, then, that so many of us long to become permanent nomads, snails with houses on our backs…” Andrei Codrescu

Transportable architecture is here defined as architecture that requires an auxiliary mobile device to facilitate movement. The most obvious and well known example is the tent, as well as modern interpretations of the tent such as the Snail Shell System. The strength of the tent as an impermanent form lies in its ability to expand and contract, as well as its lightweight configuration. Unfortunately, however, the tent is flawed in its confining scale of movement, material durability, and lack of infrastructure.

MOBILE

“I’m for portable houses and nomadic furniture. Anything you can’t fold up and take with you is a blight on the environment, and an insult to one’s liberty.” Andrei Codrescu

Mobile architecture is here defined as architecture that has embedded devices to facilitate movement; exemplified by the mobile home. Though a valiant effort in promoting movement, and flexibility of place, the mobile home embodies many shortcomings that often overshadow its advantages. Marketed as a low-income housing option, mobile homes are typically equated with low standards of living. As evidenced by the typical consumption method of the mobile home – prefabrication, delivery, permanent placement – just because something can move, doesn’t mean it will. Mobile architecture that remains static is ultimately immobile and permanent.

PNEUMATIC

“Unlike conventional architecture, which stands rigidly to attention and deteriorates, inflatables move and are so nearly living and breathing that it is no surprise that they have to be fed. All architecture has to mediate between an outer and an inner environment in some way, but if you can sense a rigid structure actually doing it, it usually means malfunction. An inflatable, on the other hand, in its state of active homeostasis, trimming, adjusting, is malfunctioning if it doesn’t squirm and creak.” Marc Dessauce

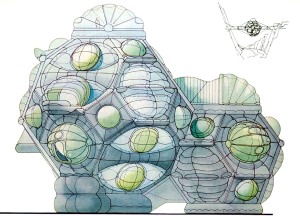

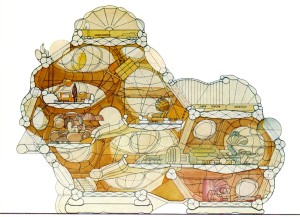

Jean Paul Jungmann’s Dyodon is an extremely flexible, provocative study in pneumatics. The structure is composed of transparent, translucent, or opaque equal-sided panels, square, hexagonal, and octagonal, which combine to form a rhombicuboctahedron. The panels can be filled with any number of materials including air, water, colored gas, helium, and earth. The Dyodon can be adapted to a wide range of terrains and climatic conditions; it can be suspended, anchored in a windy area, floated on the water, buried in the snow, or set in rough terrain inaccessible by road. The structure is mobile when floating and transportable while on land, however it is highly inefficient in its transportability, requiring machinery, infrastructure, and an immense amount of energy consumption. Most problematic is the final archaeological state of the Dyodon, calling for the injection of polyurethane that is meant to set the structure permanently.

FESTIVAL

“Transcending the dreary confines of industrial erosion…the fair created an atmosphere wholly unique, powerful, self-contained, a blaze of light and color.” David Braithwaite

Perhaps the most notorious transient festival is Nevada’s Burning Man. For the week long festival, Black Rock City appears; a temporary metropolis. Burning Man functions as an impromptu social experiment, creating a community in which institutions, service workers, and commercial transactions are entirely eliminated. Burning Man is founded on ten basic principles; radical inclusion, gifting, decommodifi cation, radical self-reliance, radical self-expression, communal effort, civic responsibility, leaving no trace, participation, and immediacy. Burning man is meant to be a lesson in impermanence; a fleeting metropolis that comes in to focus like an apparition, igniting the desert with energy briefly and intensely before it completely disappears. Laudable for its efforts, Burning Man is still problematic. Despite the ‘leave no trace’ policy, Burning Man quite literally burns a large, fabricated, symbolic man, as well as a temple and other structures built specifically for the event. The burning is in itself extremely wasteful in terms of materials, but also abruptly disputes the claim of leaving no trace; the burning of materials releases toxins into the air which, although not visible as damage, are nonetheless harmful. Further, the event is the catalyst for excessive carbon emissions resulting from the mass influx of people to Black Rock City, travelling by both plane and car.

FRAGMENT

“…Every day, every year, buildings are being erected and demolished. It happens to all buildings eventually – the celebrated and the canonized, and the innocuous and the nondescript. Most of these buildings disappear without a trace, leaving later generations unaware they ever existed. But sometimes, we are left with a trace, a scar, a remnant or fragment. These fragments…move like ghosts around us, silently incorporated.” Jo-Anne Cooper

The fragment, whether physical or intangible, exists within the fabric. Users project their memories onto spaces, activating them, creating alternate realities.

An analysis of the above examples allows us to arrive at a disturbing conclusion; what we so often believe to be physically impermanent is often static or toxic, creating invisible damages as a byproduct.

November 5, 2012

Permanence..declaration or humiliation?

Not long ago I went on a summer walk through a smiling countryside in the company of a taciturn friend and of a young but already famous poet. The poet admired the beauty of the scene around us but felt no joy in it. He was disturbed by the thought that all this beauty was fated to extinction, that it would vanish when the winter came, like all human beauty and all the beauty and splendour that men have created or may create. All that he would otherwise have loved and admired seemed to him to be shorn of its worth by the transience which was its doom.

Sigmund Freud, “On Transience”

Throughout our existence humanity has undergone a process of constant evolution; from biological to socio-cultural, and everything in between. Inseparable from these processes of evolution are technology and human subsistence methods, the two of which are ceaselessly intertwined. As human subsistence methods evolved from hunter-gatherer to pastoral and ultimately agricultural, human settlement methods evolved in parallel from nomadism to sedentism. The shift toward sedentism manifested itself architecturally by redefining the dwelling and its construction materials. Simultaneously there came a paradigm shift in the relationship between people and the things around them; other people, animals, materials, shelter, objects and the environment. Whereas nomads quite literally carried their livelihood on their backs, the sedentary dweller divulged into a life of frivolity, excess, collection, isolation, and permanence.

The shift towards a desire for permanence runs in parallel to humanity’s inability to accept, and consequent rejection of, its inescapable mortality. It is not simply evidenced by the use of materials such as stone, steel, and concrete, but also by our fascination and obsession with science, medicine, and technology as tools to make us live longer; to eliminate our biological limits in search of perpetual existence.

“Man has, as it were, become a kind of prosthetic God. When he puts on all his auxiliary organs he is truly magnificent.” [Sigmund Freud, “Civilization and its Discontents”]

Architecture is our ultimate prosthesis, our most encompassing auxiliary organ, and it has certainly not escaped our strive for longevity. From the architecture of the ancient Egyptian’s, Greek’s, and Roman’s to Hitler’s Nazi architecture, the desire for physical permanence as a sign of power has long been a part of our history, and remains so today. This desire, however, is highly problematic for a number of reasons.

LEGACY

Power struggles, at a multitude of scales, have led to the desire to leave a legacy so that we are not forgotten. Physically speaking, this requires durability and resiliency of materials to overcome erosion over time. Architecture is conceived, built, and employed within a network of constraints; a context from which it cannot be separated. Its beauty derives from its usefulness to those that it serves, but functions inevitably change over time. As functions evolve, so too does the perception of the architecture. When the pyramids were built in Egypt they were meant to preserve the body and memory of the Pharaoh buried within and to house them in the afterlife; a memorial to their power that commanded attention. A technological feat, the pyramids remained, though decay and erosion began to compromise their symbol as transcenders of time. In fear of watching history fall to pieces before our eyes, efforts began to preserve and restore, which ultimately created another major problem.

PRESERVATION

Rather than let nature take its course, preservation efforts aim to freeze, if not reverse, the effects of time. Unfortunately this creates a schism between architecture as Architecture, and architecture as relic. Static architecture is destined to succumb to decay; from the moment it is created it begins to fall apart. Arguably, structures that are being preserved no longer function as architecture; they are perceived as relics that we must protect; dead and frozen in time. Relics have mutated from architecture; they are objects whose function has become spectacle, they are novelties, stripped of their dignity and put on show. How humiliated the Ancient architect’s would be to see what their work has become; relics are a mockery.

Given the fragile state of the environment and all that it encompasses, it is becoming more and more apparent that permanence is merely a figment of our imagination. Imperceivably slow decay is decay nonetheless; all things are impermanent. This, however, does not mean that all architecture is static; efforts have been made to produce dynamic systems, impermanent and transient architecture better suited for the rapidly evolving environment and clientele that it serves. But has it been enough? Where have we been and where are we going?